By Michael Phillips | FLBayNews

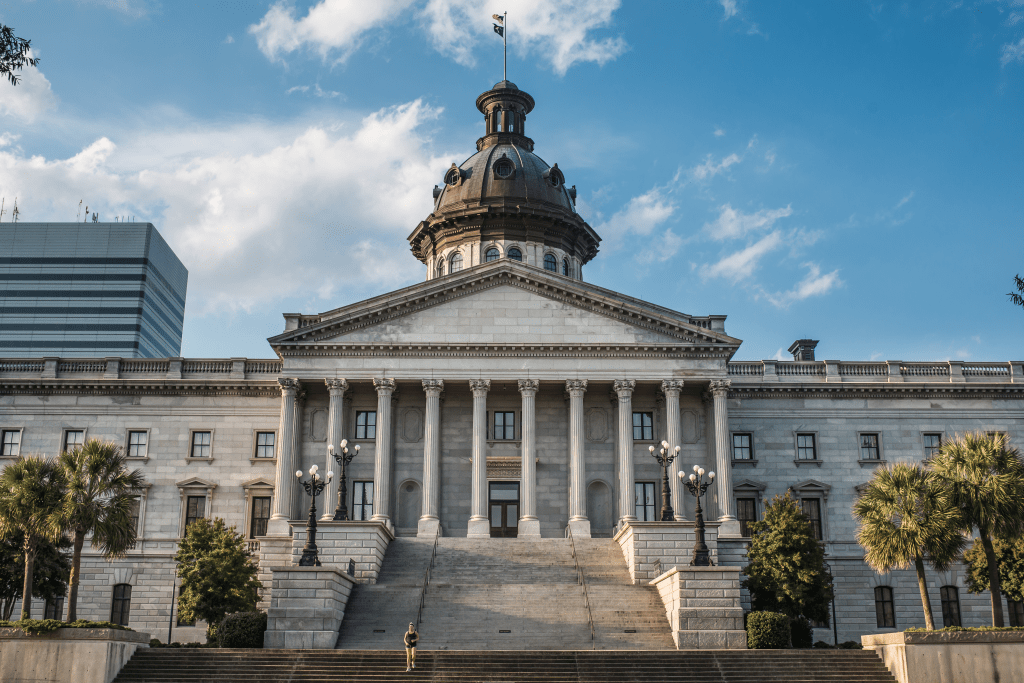

South Carolina lawmakers are preparing to debate a bill that supporters say could save lives by recognizing non-physical abuse — but critics warn it may dramatically expand government power inside family court, with serious due-process implications.

Senate Bill 702, pre-filed in December and scheduled for consideration when the General Assembly convenes in January 2026, would formally recognize “coercive control” as a form of domestic abuse under South Carolina law. The proposal represents a significant shift in how abuse is defined, how family courts weigh evidence, and how custody disputes may be decided — even without criminal convictions.

What Is S. 702?

Sponsored by Sen. Stephen Goldfinch (R–Murrells Inlet), S. 702 takes a broad approach rather than creating a new standalone crime. Instead, it weaves coercive control into multiple areas of state law — criminal statutes, divorce law, protective orders, and child custody determinations.

The bill defines coercive control as a pattern of behavior that unreasonably interferes with a person’s free will and personal liberty, including actions such as:

- Isolating someone from friends or family

- Controlling finances, movement, or communication

- Monitoring or tracking via devices

- Intimidation, degradation, threats, or reproductive coercion

The bill expands the definition of “household member” to include current or former dating relationships, not just spouses or co-parents. It also makes coercive control unlawful under domestic violence statutes, adds it as grounds for divorce, and — most significantly — requires family court judges to consider allegations of coercive control when determining child custody and a child’s “best interests.”

Importantly, these changes apply in civil and family court, where the standard of proof is far lower than in criminal court.

The Mica Miller Case and Advocacy Push

The legislation is closely tied to the 2024 death of Mica Francis Miller, whose family alleges she endured years of psychological abuse. Miller’s relatives compiled what they call “Mica’s List,” detailing alleged isolation, financial control, tracking, and manipulation — behaviors that closely mirror the bill’s language.

Advocates argue that South Carolina’s current laws focus too narrowly on physical violence, leaving victims of psychological abuse without protection until situations escalate. South Carolina consistently ranks among the most dangerous states for domestic violence fatalities, a fact supporters cite as justification for earlier intervention tools.

Some supporters have even referred to S. 702 informally as “Mica’s Law.”

A Fundamental Shift in Family Court

While the bill has drawn praise from domestic-violence advocacy groups, it also raises major concerns — especially in family court, where consequences can be immediate and life-altering.

Unlike criminal charges, family court decisions rely on a “preponderance of the evidence” standard — essentially, whether something is more likely than not. Under S. 702, allegations of coercive control could influence:

- Protective orders

- Custody and visitation rights

- Divorce proceedings

- “Best interests of the child” evaluations

All without a criminal conviction — or even criminal charges.

For critics, this is where alarms begin to sound.

Due Process and Weaponization Concerns

Center-right critics argue the bill risks creating a highly subjective framework that could be weaponized in contentious divorces and custody battles. Terms like “unreasonably interferes,” “pattern of behavior,” and “control” are open to interpretation — especially in high-conflict family disputes involving finances, communication, or parenting disagreements.

Family court already struggles with credibility disputes and competing narratives. Critics warn S. 702 could incentivize strategic accusations, particularly when custody or leverage is at stake. Online comments responding to coverage of the bill overwhelmingly express fears that ordinary marital disagreements could be reframed as abuse — with devastating consequences.

There are also broader due-process concerns. While the presumption of innocence applies in criminal law, family court operates differently. Once allegations are introduced, accused parents — often fathers — may face restricted access to their children based on claims alone, with limited procedural protections.

Lessons From Other Jurisdictions

Supporters point to states like California and Connecticut, which have adopted similar frameworks. Critics counter that international experience — particularly in the United Kingdom, which criminalized coercive control in 2015 — shows enforcement difficulties and inconsistent outcomes. Even years later, UK prosecutors have struggled to prove patterns of behavior clearly and fairly.

The concern is not whether psychological abuse exists — most agree it does — but whether broad statutory language can be applied consistently without harming innocent parties.

Bigger Questions for Conservatives

From a center-right perspective, S. 702 raises several unresolved questions:

- How far should government reach into private family dynamics?

- Are existing laws on stalking, harassment, and intimidation insufficient — or simply under-enforced?

- Should custody decisions hinge on allegations that would not meet criminal standards?

- What safeguards exist to prevent false or exaggerated claims?

Critics argue that protecting genuine victims and preserving civil liberties are not mutually exclusive — but that laws must be narrowly tailored, clearly defined, and balanced against unintended consequences.

What Happens Next?

As of December 18, 2025, S. 702 sits in the South Carolina Senate Judiciary Committee, with hearings expected early in the 2026 session. No formal opposition groups have emerged yet, but debate is likely to intensify as family-law attorneys, civil-liberties advocates, and parents’ rights organizations weigh in.

South Carolina has attempted coercive-control legislation multiple times over the past decade without success. This version’s broader integration may improve its odds — but also heightens its impact.

For concerned citizens, the question is not whether psychological abuse should be taken seriously, but whether this bill strikes the right balance between protecting victims and preserving fairness, due process, and restraint in family court.

As the debate unfolds in January, South Carolina’s lawmakers — and the public — will need to decide whether S. 702 is a necessary reform, or a well-intentioned law with consequences that reach far beyond its stated goals.

Leave a comment